Built for the Frontlines

of Legal Opportunity

Because the future of law isn’t reactive - it’s strategic.

.avif)

Rising consumer demand for environmental accountability has led to an increase in greenwashing class actions.

But these cases are difficult to win, with courts often dismissing claims at early stages due to insufficient evidence, particularly those involving carbon offsetting. According to TINA.org, just 6% of US greenwashing cases involve false or misleading carbon reduction claims, a small percentage that reflects the evidentiary challenges inherent in winning or settling such claims.

However, the emergence of sophisticated climate intelligence technology is changing how attorneys approach these cases. This technology provides the evidentiary foundation that has long been missing, particularly in carbon offset litigation, for attorneys to substantiate claims with data that can withstand judicial review and substantially improve litigation outcomes.

In the US, there is no private right of action to hold corporations accountable for inadequate or ineffective climate mitigation measures. As a result, private lawsuits targeting misleading environmental marketing, also known as greenwashing, are typically brought under consumer protection and false advertising laws.

Plaintiffs must prove they were misled and suffered economic harm from being misled.

But many suits never survive the pleadings stage: they’re either thrown out for lack of standing or failure to show that the company’s marketing caused a tangible loss. Greenwashing lawsuits that do survive the litigation process have resulted in low-modest damage awards, making them less appealing to attorneys.

A recent Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance article discusses several types of greenwashing cases filed between 2023 and 2025, most of which are already dismissed.

One example includes Environmental Working Group v. Tyson Foods, where the court allowed an environmental group’s claim that Tyson’s net-zero by 2050 goal and “climate-smart beef” program were misleading due to insufficient plans to meet these goals.

Another case is Gyani v. lululemon Athletica, where the court dismissed a consumer class action against lululemon, ruling that the plaintiff failed to demonstrate that the company's “Be Planet” campaign misleadingly implied its products were environmentally friendly enough to justify a price premium.

Carbon offset cases are a particularly challenging type of greenwashing case that’s difficult to prove for 3 main reasons:

While carbon offset claims are difficult to prove, climate intelligence technology is now providing evidence of failed corporate offset programs that is more difficult for defense counsel to refute.

This includes satellite imagery, deforestation monitoring, geospatial mapping, and carbon accounting analyses exposing false corporate climate claims. For example, satellite data can reveal that ARR projects (forests credited with carbon sequestration) show little to no tree growth, or remote sensing of a REDD project might show that the real historic deforestation rate is much lower than stated, leading to overestimation of generated credits.

This is raising the bar for corporate climate accountability.

Courts are now being asked whether companies need to thoroughly investigate offset projects before making carbon-neutral claims, rather than simply accepting third-party certifications at face value.

And with stronger evidence, more law firms are going to pursue similar cases and companies will actually need to substantiate their sustainability claims before using them as part of their marketing strategies.

It’s worth noting, however, that some have raised concerns about unintended consequences. Strict scrutiny over carbon reduction claims might discourage legitimate offset efforts, creating tension between encouraging genuine climate action and penalizing dishonest greenwashing. Courts will need to balance holding companies accountable without deterring good-faith environmental efforts.

.avif)

Two recent greenwashing cases, both class actions, against Apple and British American Tobacco (BAT) involve claims of carbon neutrality and both are pioneering the use of climate intelligence as evidence in court.

In late 2023, Apple began marketing its Apple Watch Series 9, SE, and Ultra 2 models as the company’s “first-ever carbon neutral products.” Apple touted that it had cut the watches’ emissions by 75% and would “use high-quality carbon credits to address the small amount of remaining emissions,” resulting in a carbon-neutral product.

But in February 2025, Apple was sued in a putative class action claiming these carbon-neutral claims were “false and misleading.” According to the complaint (Dib v. Apple), the forest projects from which Apple purchased carbon credits “fail to provide genuine, additional carbon reductions” because the projects, one in Kenya’s Chyulu Hills and one in China’s Guizhou province, don’t actually absorb extra CO₂ beyond what would have happened anyway.

.avif)

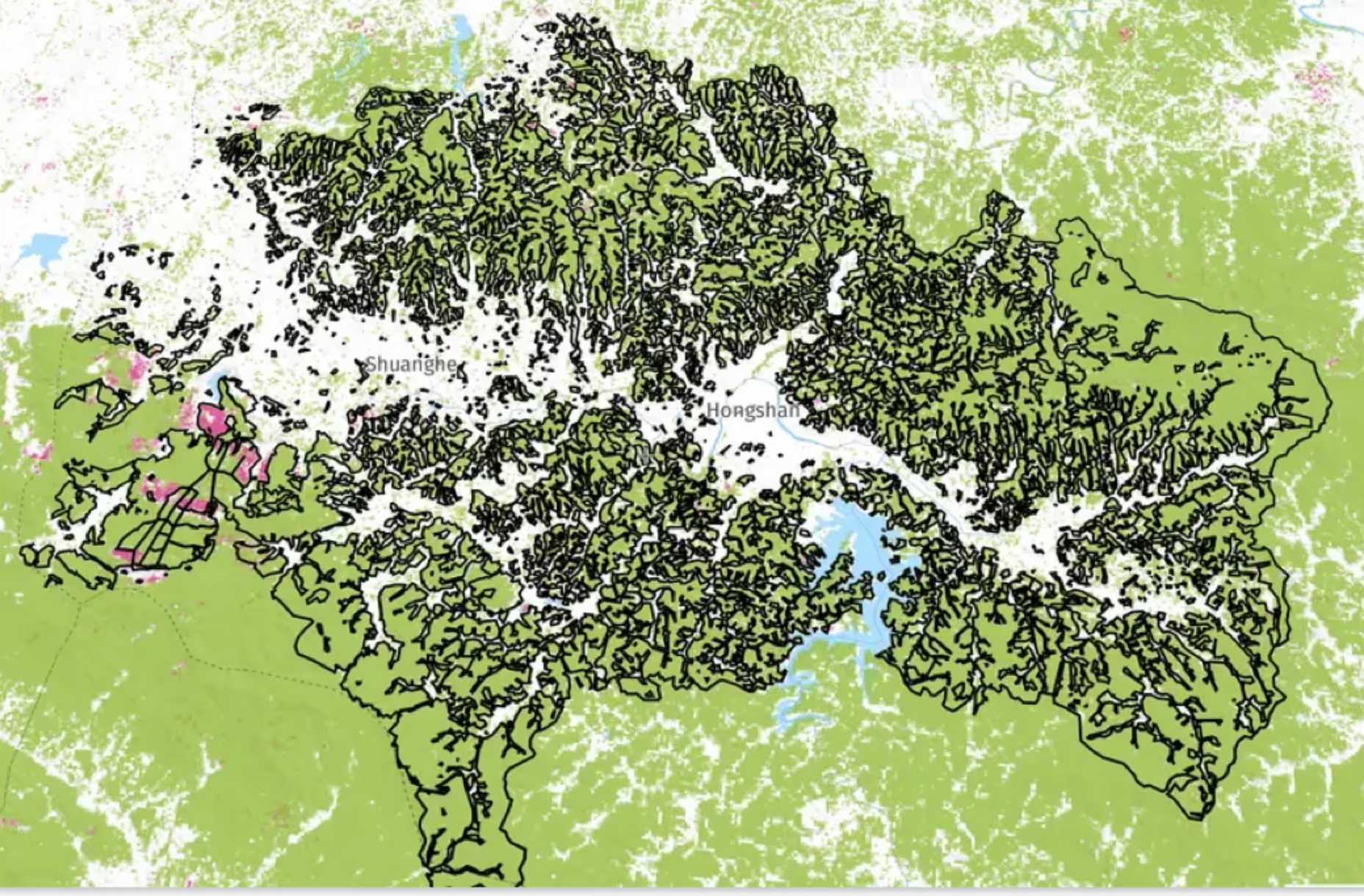

Plaintiffs provided detailed geospatial mapping, satellite analysis, and forest carbon data, to claim that 78% of the forest area in the China project was “already covered by trees” before the project began, and that much of the Kenyan project lies within a national park established in the 1980s. This implies that the claimed carbon reductions would have occurred regardless of Apple’s involvement or the project’s existence.

The complaint alleges that Apple’s credits not only failed the key test of additionality, but analysis revealed that the claimed historic deforestation rate is over 60 times higher than the observed actual rate.

Lead plaintiffs’ attorney, Fletch Trammell, says:

“We can demonstrate that those carbon offsets are completely bogus. There was no carbon neutrality, which makes that claim untrue."

In May 2025, BAT was hit with a $5 million class action lawsuit (Bell v. R.J. Reynolds Vapor Co.) accusing the company of falsely marketing its Vuse e-cigarettes as carbon neutral.

According to climate intelligence detailed in the complaint, 84.72% of BAT’s offsets come from four forestry projects in Uruguay and China, all of which “fail to provide genuine, additional carbon reductions.” For example, the Guanaré Forest Plantations Project in Uruguay would have been established regardless of carbon credit funding, while the three Chinese projects protected forests that faced “negligible deforestation risk prior to the projects, meaning that the emission reductions claimed would have occurred anyway.”

An independent agency concluded that “out of the approximately 500,000 carbon credits that Defendants have purchased since 2020, nearly 80% of them correspond to projects that have either a ‘moderately low,’ ‘low,’ or ‘very low’ likelihood of achieving actual emissions avoidance or removal.”

Like the Apple case, the BAT lawsuit argues the defendants had an obligation to independently verify that the offset projects met basic additionality standards, instead of blindly trusting a third-party certification.

Greenwashing litigation is evolving from a niche practice into an evidence-driven legal strategy with significant potential.

Climate intelligence technology, including AI, satellite analytics, geospatial mapping, and other GIS tools, equip attorneys to pursue greenwashing cases with greater strategic precision and stronger evidentiary support. As this technology proves its effectiveness, we anticipate more greenwashing class actions, higher settlements, and increased corporate accountability.

Darrow's legal intelligence platform provides attorneys with the climate data and analytical tools necessary to build strong carbon offset class actions. Firms can evaluate potential claims and pursue litigation with greater confidence in their evidence base. As companies continue making environmental claims without adequate substantiation, having access to reliable climate intelligence becomes essential. Law firms seeking to expand their environmental litigation capabilities can leverage this technology to hold corporations accountable for false sustainability claims.

This Might Interest You: