Built for the Frontlines

of Legal Opportunity

Because the future of law isn’t reactive - it’s strategic.

.png)

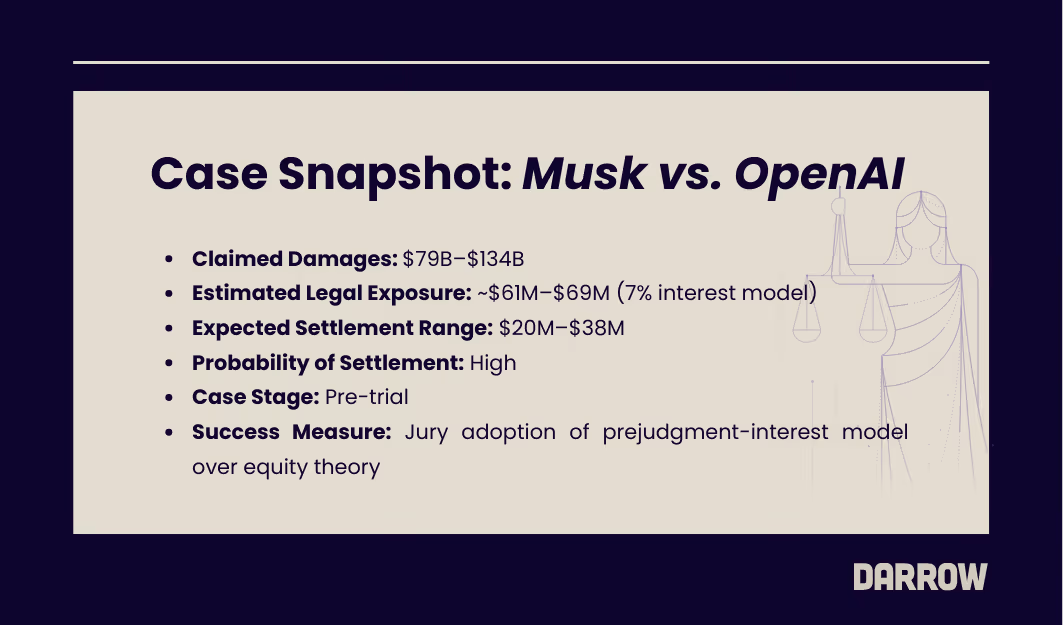

Elon Musk’s lawsuit against OpenAI has produced one of the largest damages claims ever asserted in Silicon Valley, with demands reaching up to $134 billion. From the perspective of Darrow's Case Assessment and Valuation Team, the headline number tells the wrong story, obscuring the far more limited scope of real legal exposure and expected recovery.

Musk co-founded OpenAI in 2015 as a nonprofit dedicated to developing AI “for the benefit of humanity.” He donated approximately $38 million, which he estimates represented roughly 60% of OpenAI’s early funding, along with recruiting assistance, business advice, industry contacts, and credibility. He departed in 2018 after a breakdown over governance and control, including proposals involving Tesla.

In 2019, OpenAI restructured, creating a for-profit subsidiary under a “capped-profit” model and entering into a strategic partnership with Microsoft, which has since invested more than $13 billion. In 2025, OpenAI completed its transition into a for-profit Public Benefit Corporation (PBC). OpenAI’s valuation is now at approximately $500 billion with Microsoft holding the largest stake of equity at 27%.

Musk alleges OpenAI’s leadership always intended to abandon the nonprofit structure, fraudulently inducing his donations. OpenAI counters that Musk participated in for-profit discussions before his departure and is now using litigation to hobble a competitor to his own AI company, xAI.

What began as a disagreement over nonprofit governance has transformed into Musk arguing that the defendants realized “wrongful gains” from his early support of OpenAI, effectively asking the court to retroactively treat his early support of OpenAI as if it were a venture investment rather than a donation.

The case will proceed to a jury trial in April 2026, with core claims surviving dismissal including fraud, breach of charitable trust, and unjust enrichment.

Elon Musk was undeniably one of OpenAI’s earliest and most significant financial supporters. According to recent court filings, Musk’s documented personal contributions totaled approximately $38 million. These include five quarterly grants of $5 million in 2016–2017, roughly $12.7 million in rent payments for OpenAI’s office space between 2016 and 2020, and the provision of four Tesla vehicles to key employees.

When Musk gave $38 million to OpenAI, he made donations to a 501(c)(3) nonprofit which, as a matter of law, carries no expectation of financial return. Accordingly, the central issue in Musk v. OpenAI is not whether Musk played an important role in OpenAI’s early development, but whether a charitable donation can later be recharacterized as an equity-like investment once a nonprofit evolves into a commercially valuable enterprise.

Musk’s damages theory begins with the current value of OpenAI’s for-profit entity, applies the nonprofit’s ownership stake in that entity, and then assigns 50–75% of the resulting value to Musk’s alleged monetary and non-monetary contributions. Using this approach, Musk claims OpenAI’s wrongful gains range from approximately $65.5 billion to $109.4 billion, with a similar adjusted methodology producing claimed wrongful gains of $13.3 billion to $25.1 billion for Microsoft.

OpenAI, by contrast, maintains that even if liability were established, any recovery should be limited to the nominal value of Musk’s donations, rather than any share of OpenAI’s subsequent enterprise value.

If the court applies conventional fraud principles, remedies would likely include restitution of Musk’s donation, interest, and perhaps disgorgement of any specific benefits that can be directly traceable to his contributions.

Microsoft’s involvement increases the visibility of the dispute, but it does not materially change the damages analysis, which remains anchored to the treatment of Musk’s original charitable contributions.

Under the California Constitution, Art. 15, § 1, the default rate for claims involving allegations of fraud and breach of trust is 7% per year.

Prejudgment interest may be awarded on either a simple or compound basis under California law, depending on the jury’s findings. While compound interest is typically reserved for cases involving clear fiduciary breaches, the presence of fiduciary-type allegations and claims of constructive fraud in this case introduces some uncertainty.

Presenting both simple and compound interest scenarios, estimated damages based on Musk’s contributions are approximately $61.3 million assuming simple interest, or up to $69.2 million assuming annual compounding through a 2026 judgment.

Punitive damages may also be available if fraud is proven, but they would almost certainly be measured in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, not tens of billions.

In practice, the large majority of cases resolve through settlement rather than trial, and resolution is typically reached for a portion of estimated damages rather than the full theoretical amount.

In this case, settlement discussions would likely be anchored around the nominal amount of Musk’s donations, approximately $38 million.That figure represents roughly 55–62% of estimated damages, depending on how prejudgment interest is calculated, placing it at the upper end of settlement outcomes typically observed in the data.

While historical settlement data indicate that cases surviving a motion to dismiss tend to carry both a higher likelihood of settlement and higher expected settlement values, recoveries at this level remain relatively uncommon. The unusually high level of media attention and reputational sensitivity surrounding this dispute further influence settlement dynamics, increasing the incentive for both sides to avoid prolonged litigation. Taken together, these factors suggest a reasonable settlement range in this case of approximately $20 million to $38 million.

Taken together, these factors suggest a reasonable settlement range in this case of approximately $20 million to $38 million.

While OpenAI’s nonprofit origins and subsequent transition make this case factually distinctive, similar disputes provide a useful lens for how courts and parties have resolved comparable disputes in practice. The settlement dynamics in ConnectU v. Facebook and eBay v. Newmark reflect recurring patterns seen across high-profile technology and governance disputes.

In the Facebook litigation, popularized in the movie The Social Network, ConnectU co-creators Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, along with Divya Narendra, alleged that Zuckerberg stole their idea and proceeded to create thefacebook.com before they had a chance to launch ConnectU. Although plaintiffs claimed they were foundational to what later became a massively valuable company, their legal entitlement to valuation-based damages was limited. The case ultimately settled for approximately $65 million, not because a court was likely to award damages tied to Facebook’s enterprise value, but because prolonged litigation posed reputational, discovery, and operational risks that Facebook wanted to contain.

In the eBay case, the dispute focused on control and governance, with the court making clear that once a company operates as a for-profit, founders cannot rely on mission-based arguments to avoid standard corporate obligations, a ruling that ultimately increased pressure toward a later confidential settlement.

Musk v. OpenAI reflects the same dynamic, where the realistic damages exposure is limited, but the strategic and reputational costs of continued litigation may push the parties toward settlement despite the outsized claims.

Musk v. OpenAI is not a class action, so if it settles, the terms will likely remain confidential. The case nonetheless serves as a useful reminder that eye catching damages demands often bear little relationship to actual legal exposure or likely settlement outcomes. But reducing this case to the dollar misses the point. Musk’s lawsuit is likely to be remembered less for the size of the claim or the court’s ruling than for clarifying the boundaries between charitable giving and venture investing. It forces a reckoning with how mission-driven organizations evolve once commercial incentives take over.

But reducing this case to the dollar misses the point. Musk’s lawsuit is likely to be remembered less for the size of the claim or the court’s ruling than for clarifying the boundaries between charitable giving and venture investing. It forces a reckoning with how mission-driven organizations evolve once commercial incentives take over.

A “win” for Musk goes well beyond money. The case reinforces his long standing critique of OpenAI’s transformation and accelerates a broader public conversation around AI ethics, governance, and accountability. Perhaps most importantly, it strips away any remaining ambiguity: OpenAI is now widely understood as a for profit enterprise, not a nonprofit experiment.

Even if the court awards only a fraction of the damages sought, or none at all, Musk may already have secured a strategic victory. This lawsuit was never really about the money. It was about shaping the narrative, and forcing the world to confront what it means when technology built “for humanity” is ultimately governed by profit.

This Might Interest You: